Central Park in the Dark Revisited

From about 2005 to about 2009, I had a wonderful time getting to know Maire Winn and her friends, affectionately known as “The Regulars”. During the daytime they mainly watched Pale Male, his mates and their offspring. After dark, I would join them on their nocturnal adventures, observing owls, insects, and mammals. They were passionate naturalists who were thrilled to learn about the natural world through field work and research.

My fondest memories of the gang were our owl-watching adventures. Each time we spotted an owl, we discovered something new about these fascinating creatures.

Shortly after the publication of her last book, Central Park in the Dark in 2008, Marie and her friends stopped visiting the park regularly. Two of “The Regulars” had passed away, others faced health challenges, and one happily fell in love and moved to Florida.

Marie Winn passed away at the end of 2024.

She updated her book about Pale Male, his mates, and their offspring, Red-tailed in Love, for a tenth anniversary edition. I’ve often wonder what a sequel to or a revised edition of Central Park in the Dark would have included, if Marie and her friends had been able to continue their nocturnal prowls in Central Park.

The subtitle of Central Park in the Dark was “More Mysteries of Urban Wildlife.” Marie Winn, an accomplished nature writer, described the park’s wildlife through captivating adventure stories that showcased both the observers and their discoveries. Without resorting to heavy-handed explanations, Winn imparted valuable lessons about how to be a naturalist. She demonstrated how to harness one’s innate curiosity and embark on a journey of discovery, exploration, and research. Winn also illustrated the iterative nature of scientific inquiry, where initial hypotheses are refined or discarded based on new discoveries.

Since the book’s publication, the park has welcomed a new wave of visitors. In the past 17 years, we’ve had two extraordinary owls: a rare Snowy Owl and a non-native Eurasian Eagle-Owl that was released from the Central Park Zoo. Additionally, we’ve had extended stays by Northern Saw-whet Owls, a Barred Owl, a Great Horned Owl, and most recently American Barn Owls. Each of these owls would have deserved its own chapter in a new or revised book.

Other nocturnal birds, such as Black-crowned Night-Herons (who regularly feast on the park’s buffet of Brown Rats), Nightjars, and American Woodcocks, are also being observed more closely at night. These birds would have been described as antidotes sprinkled throughout the new chapters.

The park has also seen some new mammals. Eastern Cottontail Rabbits have become common, appearing around the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. After three brief visits by coyotes over a decade ago, we now have a pair of resident Eastern Coyotes. Southern Flying Squirrels are being seen regularly with the aid of thermal monoculars. In a revision edition or sequel of the book, I’m sure flying squirrels and rabbits would have each gotten a new chapter, while the coyotes might have required multiple chapters.

Since the book’s publication, technology advancements have greatly aided nocturnal observations.

- Digital cameras now enable photographers to capture wildlife in extremely low light conditions.

- High-resolution thermal monoculars have become available, enabling naturalists to locate and identify flying squirrels, owls and coyotes even in complete darkness.

- Bat detectors have advanced significantly, with devices like the Wildlife Acoustics Echo Meter Touch 2 that plug into smartphones, allowing users to easily hear bat echolocations and automatically identifies the bat species.

- Smartphone apps such as Merlin (sound and photo identification), iNaturalist (a peer-to-peer naturalist community), and Sky Guide (a star and planet guide) have simplified the process of identifying birds by sound or photographs, identifying plants, insects and animals, and observing the night sky.

I’m certain Marie and her friends would have been thrilled to embrace these new technologies. Any new stories or revisions of older ones would have included mentions of these innovative tools.

A revised edition of or a sequel to Central Park in the Dark would have most likely included the following updates to existing chapters or additional new chapters.

Marie’s first chapter, “Party-Crashers and Flying Mammals”, includes notes about the Red-tailed Hawks, Pale Male and Lola, along with antidotes about raccoons and bats. Each of these topics would have received updates.

- While the nest was returned to 927 Fifth Avenue, due in large part to Marie Winn’s advocacy, Pale Male and Lola’s nests failed. Eggs were laid, but they did not hatch. It led to a lot of discussion and second guessing about the cradle that had been installed to support the new nest.

In the end, it turned out Lola had become infertile. When Lola died and Pale Male mated again, there were eyasses (hawk chicks) once more. This resulted in several successful clutches before the nest was unproductive once again. Eventually Pale Male passed away. Marie would have written beautifully about this post-Lola era and published a wonderful obituary about Pale Male’s life. - Raccoons, which are written about benevolently, became a problem in 2009-2010 due to a rabies outbreak that ended up with two people being bitten, a person walking a dog, and hot dog vendor. Over one hundred raccoons were found dead, and others were euthanized. Thankfully, many were saved from infection through a vaccination program.

Unfortunately, due to poor trash management and park patrons feeding the raccoons, raccoons and gray squirrels are overpopulated in the park, displacing birds and other animals that use tree cavities. Raccoons are a more complicated subject than the few pages they received in Marie’s book. - Studying the park’s bats became much easier with the introduction of Wildlife Acoustics Echo Meter Touch 2 device. The meter attaches to a smartphone and listens for a bat’s echolocation. Using software, the meters determine the species of bat based on its echolocation pitch and pulse rate. No longer is tagging along with a BioBlitz necessary; anyone can now easily identify the park’s bats.

Since Marie’s book was published White-Nose Syndrome has decimated the Little-brown Bat population and reduced the number of Big-brown Bats. However, bats continue to be abundant during the warmer months and are easy to spot.

At the Conservatory Water (also known as Model Boat Pond), on late summer evenings, Chimney swifts feed on insects and drink before roosting in a nearby Fifth Avenue Chimney. As darkness sets in, the swifts are replaced by feeding bats. The Eastern Red Bats are the first to arrive, followed by Silver-haired Bats, Big Brown Bats, and Tricolored Bats. It’s a delightful evening, and I’m certain Marie and her friends would have enjoyed adding this to their nocturnal activities in Central Park.

Marie’s second chapter, “The Ghost of Charles”, includes notes about numerous owl species, owl ethics, flying squirrels, and white-footed mice. (I regret to say that I started birding a year after Charles Kennedy passed away and never had the opportunity to meet him. From all accounts, he was an incredible person.)

- Owls would have certainly warranted many new chapters. Numerous Northern Saw-whet Owls the Barred Owl that was named Barry and the Great Horned Owl, Gerald(ine) with a damaged leg, the once-in-a-century Snowy Owl visit during COVID-19, Flaco, the Eurasian-Eagle Owl released from the zoo, and the American Barn Owls of 2025-2026 are some of the notable owls that resided in Central Park over the recent years.

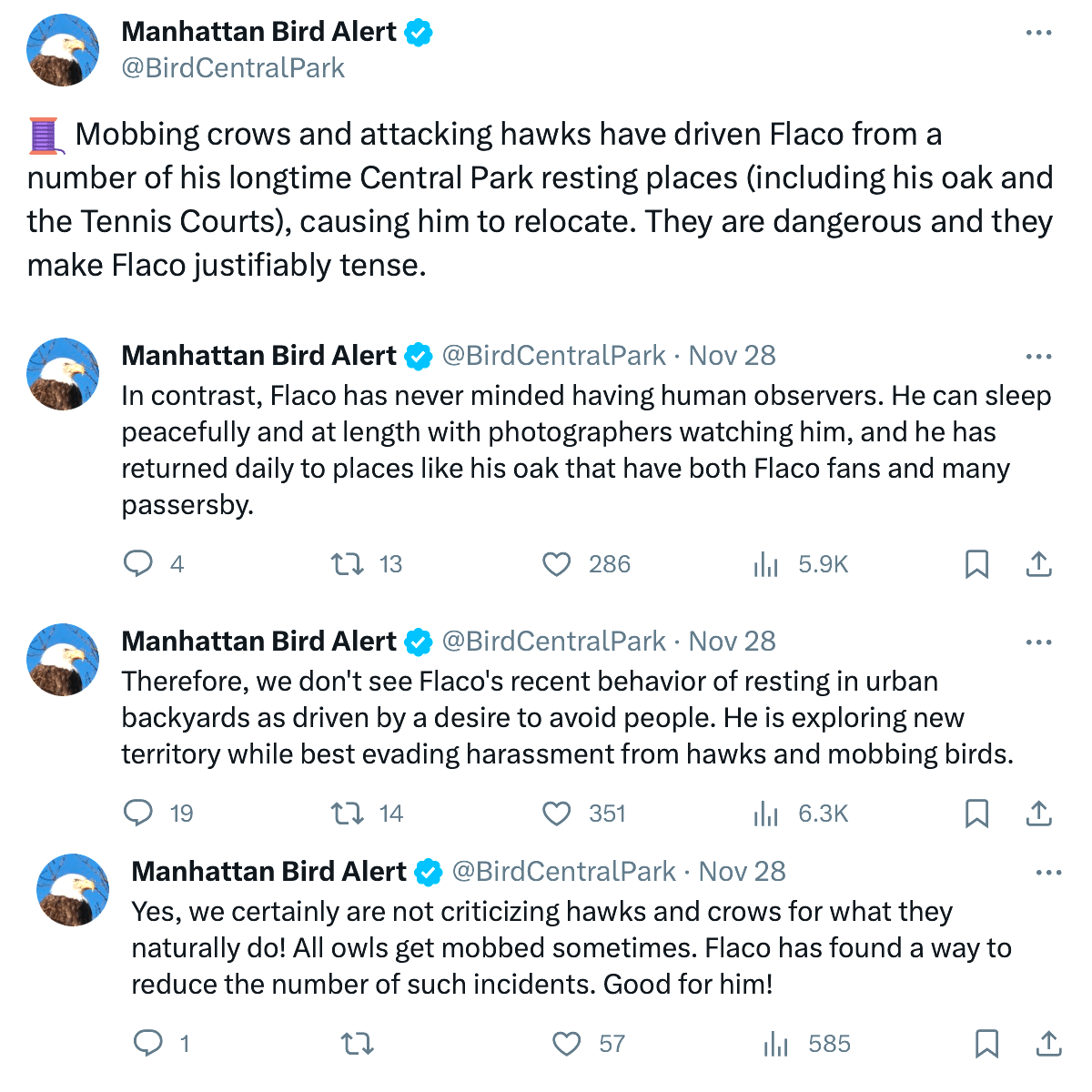

- Owl ethics have become a challenging and divisive issue in Central Park. Social media facilitated the rapid sharing of owl locations, and social media influencers exploited owls to boost their feeds. The “celebrity bird” phenomenon led to crowds gathering around certain owls, leading to their harassment. When wild animals are used for entertainment, humans unfortunately often exploit them.

Additionally, people often respond to wildlife as though they are pets, leading to unintended consequences such as feeding harmful food to the animals or the unwise protection of invasive species such as feral cats. It’s a complex issue.

Central Park in the Dark was a lighthearted story. In a revision, discussing ethics wouldn’t be a lecture in a dedicated chapter. However, I suspect Marie would have added a few paragraphs here and there to illustrate the problems and challenge readers to reflect on their own ethics. - In this chapter, flying squirrels are described as almost mythical creatures in a few paragraphs. Thermal monoculars have made it possible to finally study them. The park is home to numerous Southern Flying Squirrels making them a subject worthy of a new chapter.

Chapters three through six primarily discuss moths and insects, but they also mention Black Skimmers, Astronomy, and Kingbirds.

- Studying moths became easier in recent years. While used copies of Covell’s Moths guidebook can still be found for sale online, applications such as iNaturalist has made it much easier to network with other amateur Lepidopterists to identify moths.

- Black Skimmers continued to appear, but more rarely. They used the Conservatory Water, also known as The Model Boat Pond, for a few years before the Central Park Conservancy began adding dye to the water annually. Most sightings are now on The Lake, often with the skimmers going under Bow Bridge.

- Eastern Kingbirds continue to nest on the west side of Turtle Pond, usually having two or three offspring each year.

- Astronomy remains an activity in Central Park, with notable events such as supermoons, planet convergences, comets, and eclipses. New smartphone apps, such as Sky Guide, make it easier to identify planets and constellations.

Chapter 7, “Birds Asleep,” details morning bird sounds, jokes about a rabbit (which would have been a chapter in a revised book), comets, and American Robin and Common Grackle roosts. Chapter 8, “Pale Male Asleep,” discusses the expansion of Red-tailed Hawk nests in New York City and the Woodland’s Committee.

- Merlin, Cornell University’s sound and visual identification tool, would now be a central topic in this section about bird sounds. It’s a great tool for discovery, but like any A.I. tool it’s not always accurate, so it’s important to question its results.

- In an era where tools like eBird, social media, and Merlin risk transforming birdwatching into a mere game akin to Pokémon Go, I’m certain Marie would have written about how to effectively utilize tools like Merlin, not as a crutch, but as a means to enhance observations.

- After many Common Grackle roost trees were damaged in a winter storm, they were cut down and replaced with a different species. Consequently, there’s no longer a massive influx of birds at dusk at Grand Army Plaza.

- Red-tailed Hawk nests, while experiencing a recent decline in Central Park, are still doing well throughout the city. A discussion of the history of the other Red-tailed Hawk nests in Central Park, over the last fifteen years would be an interesting update.

- Regrettably, the Woodland’s Committee no longer exists. The Central Park Conservancy has ceased its interest in meeting with the naturalist community.

Chapter 9 through 12, are primarily about owl watching. The reintroduction of the Eastern Screech-Owl failed, and although Marie generally wrote positive accounts, a dedicated chapter would be necessary to detail the outcome of the project. When the reintroduction was first proposed, Peter Post Peter Post expressed concerns at a Woodlands Committee meeting that we shouldn’t reintroduce them if we don’t first understand why they died out. His concerns proved warranted. Factors such as rodenticides, car collisions, predation and cavity contention with over-fed squirrels resulted in most of the owls dying, with a few dispersing to areas outside of the park. By 2012, there were no longer any Eastern Screech-Owls in the park.

Marie Winn’s writing beautifully captured the joy of studying nature. While her tales occasionally contained anthropomorphic elements that some readers found excessive, she conveyed to her readers the immense pleasure derived from the process of discovery. She educated New Yorkers about the abundance of nature within the city that could be enjoyed and explored. Her books inspired many New Yorkers to embrace the natural world and become naturalists.

Central Park continues to be a magical place to study wildlife in both the day and at night.

It’s too bad she wasn’t able to revise or to have written a sequel to Central Park in the Dark. I bet Even More Mysteries of Urban Wildlife would have been a best seller.